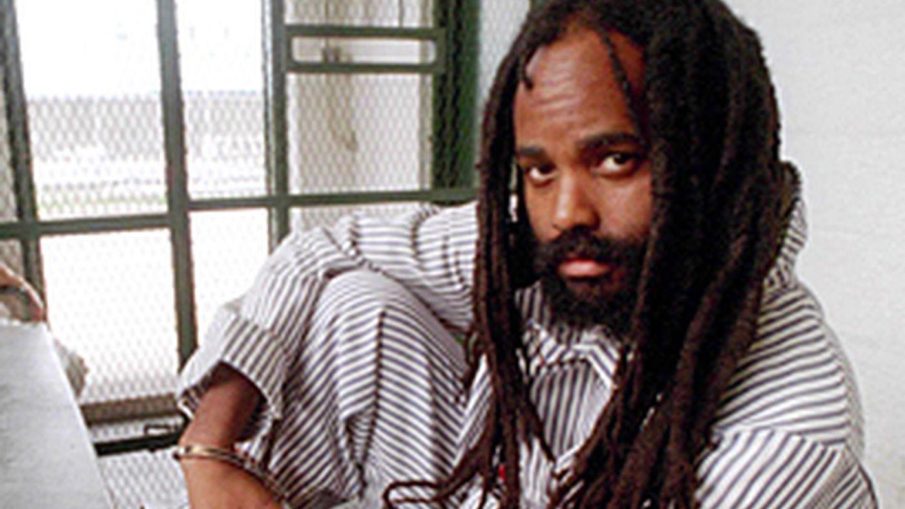

I had the honor and privilege to meet with Jamal Cook, the son of Mumia Abu-Jamal, and hear him tell what he knows about his father’s story. Mumia Abu-Jamal, born Wesley Cook, is a political activist and journalist who was convicted of murder and sentenced to death in 1982.

Abu-Jamal was convicted for the 1981 murder of a Philadelphia police officer by the name of Daniel Faulkner. He became widely known while on death row for his writings and commentary on the criminal justice system in the United States.

After numerous appeals, his death penalty sentence was overturned by a federal court. In 2011, the prosecution agreed to a sentence of life imprisonment without parole. He entered the general prison population early the following year.

Mumia Abu-Jamal adopted the surname Abu-Jamal (“father of Jamal” in Arabic) after the birth of his first child, son Jamal, on July 18, 1971. Jamal is the oldest out of eight children. Abu-Jamal also has several grandchildren. several grandchildren. How does he keep in touch? Some grandchildren he has never seen.

“My father tries to keep contact the best that he can, phone calls, letters, even painting pictures and sending them through the mail. He always lets it be known that he loves us,” Cook said. Abu-Jamal’s father William died when he was nine; his mother Edith died in February 1990, eight years after he was imprisoned. Family is very important to him.

Abu-Jamal has been locked up since he was 27. He is now 65. The story of how he ended up here has been told often. At the age of 14 in 1968, Abu-Jamal became a member of the Black Panther Party. Around this time, however, most of the party’s leaders were either dead or in jail.

Abu-Jamal left the Black Panther Party in October 1970, but he kept the tools and principles he learned during his tenure. He eventually served as president of the Philadelphia Association of Black Journalists. He supported the MOVE Organization in Philadelphia and covered the 1978 confrontation in which one police officer was killed. The MOVE Nine were arrested and convicted of murder in that case.

In the early hours of Dec. 9, 1981, Abu-Jamal was out in his cab when he saw his brother, Billy Cook, being stopped by a police officer, Daniel Faulkner. A struggle ensued, during which Cook testified that Officer Faulkner assaulted him. Abu-Jamal got out of his cab to assist his brother and minutes later, Faulkner had been shot dead and Abu-Jamal was slumped nearby with a bullet wound to the chest, his own gun not far away.

At his trial in 1982 it appeared to be an open and shut case. Abu Jamal was a former Black Panther with a history of antipathy towards the police (although no criminal record). There was a white police officer dead. There were a succession of eyewitnesses who testified that Abu-Jamal was the killer. And the icing on the cake: there was a confession made by Abu-Jamal himself at the hospital where he was taken for treatment.

However, some inconvenient facts were obscured. Abu-Jamal’s gun was never tested to see whether it had been fired; his hands were never swabbed to establish whether he had fired it; and his gun’s bullets were never solidly linked to those that killed Faulkner.

Also, of the three witnesses, one has since admitted to lying under police pressure, another has disappeared amid evidence that she too was under duress, and the third initially told police that he had seen the killer run away but changed his story.

Evidence from others who said they saw a third man running away was played down. Evidence of Abu-Jamal’s confession was equally shaky. Although two witnesses testified to hearing him shout, “I shot the mother*** and I hope the mother*** dies,” the doctors who treated him insist that his medical condition made such a thing impossible.

Neither of the two police officers who claimed to have heard the confession reported it until more than two months after the shooting — after Abu-Jamal had made allegations of being abused by police during his arrest. On the contrary, one noted in his log at the time that “the negro male made no comment” in the hospital.

The trial judge, Albert Sabo, was a former member of the powerful police union, the Fraternal Order of Police, known to favor prosecutors. He overturned permission Abu-Jamal had obtained to represent himself, excluded him from much of his own trial, and presided over jury selection in which the majority of black candidates were removed.

A court stenographer overheard Sabo telling a colleague: “I’m going to help them fry the n*****.” Since 1982, the murder trial of Abu-Jamal has been seriously criticized for constitutional failings; many believe that he is innocent, and many also opposed his death sentence. The Faulkner family, public authorities, police organizations, and other groups believe that Abu-Jamal’s trial was fair, his guilt undeniable, and his death sentence appropriate.

Jamal Cook, just like many others, believes that his father is a victim of a racially unjust judicial system. No one knows exactly what happened that evening except for the individuals involved. What we do know is that Mumia Abu-Jamal was never afraid to voice his opinion or stand up for what is right, even if it cost him his life.

When his death sentence was overturned by a federal court in 2001, he was described as “perhaps the world’s best-known death-row inmate” by The New York Times. During his imprisonment, Abu-Jamal has published many books and commentaries on social and political issues. His first book is one of my personal favorites, “Live from Death Row.”